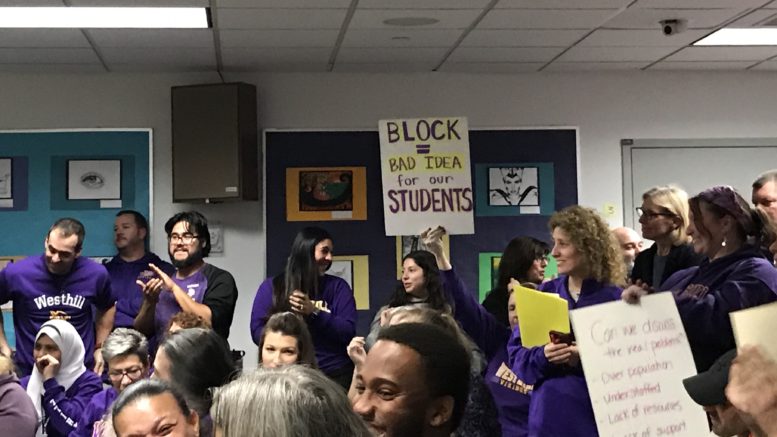

On Tuesday, November 26, the Board of Education (BOE), teachers, students, and parents all met to discuss the future block scheduling and its implications.

Teacher, student, and even custodian speakers stood at the front of the room to voice their concerns as the BOE listened and took notes. Each of the 28 speakers were given a time limit of three minutes during which many of them demonstrated their disfavor of the block scheduling proposal.

In the 2020-2021 school year, Westhill and Stamford High are planning to implement a schedule of four periods of 88 minutes on a two-day rotation, which has been commended by the Academy of Information Technology & Engineering (AITE) staff and students, who have been operating under this schedule since the 2002-2003 school year. According to an article and survey from June 2019 by AITE journalist Campbell Beaver, 91 percent of students at AITE like the schedule and feel more prepared for college.

Teachers remain wary. According to Dr. Migiano, a Westhill chemistry teacher, AITE students are less proficient than Westhill students in STEM classes. Westhill has an 82 percent proficiency rate in chemistry, while AITE has a 12.2 percent proficiency rate. In geometry, Westhill has an 84.6 percent proficiency rate, while AITE has a 45.6 percent proficiency rate.

Advanced Placement (AP) classes are also going to take a blow, as the block scheduling will cut out 13 hours of instructional time per class each year. Already challenging and densely-packed curriculums will be rushed, and material might not be finished by the time the AP exam rolls around in May.

“A specific class I take, AP Calculus, is one of the most difficult and advanced classes in the school. Currently with the [50] minute classes, I feel burnt out and exhausted after lessons. Our class typically begins at the late bell and runs to the very last minute. We are racing to finish the curriculum as it is,” Divya Gada (’20) said.

“You can not shove a curriculum down their throats and expect them to do well,” Migiano said.

Teachers also feel that they have not been included in the planning and implementation process. Many feel as if their worries and requests have not been considered during professional development.

“Promises that have been made to the teaching staff have not been fulfilled,” Westhill English teacher Ms. Tobin said.

Teachers will be met with an additional workload, having to not only adjust the curriculum for the block scheduling, but also having to prepare to teach a sixth class. The teachers at other schools that are proponents of and have adopted block scheduling only teach five classes. A sixth class places additional stress on the teachers, and might inversely lower quality of teaching.

“All of these supposed benefits [of the block scheduling] do not apply to us,” said Mr. Weintraub, a Westhill math teacher who has taught for 13 years.

It has been said that the people behind the block scheduling creation and implementation do not step foot inside of the classroom and are making decisions on behalf of the people who are in it everyday.

“We are experts in our fields…why should our opinions not matter?” Genie Valentine, a Stamford High teacher who has taught for 24 years, said.

If the new schedule was adopted, students would no longer be offered study hall periods. Instead, “What I Need” (WIN) periods would be offered where students receive mentoring.

According to district proposals, block scheduling is to be implemented with graduation rates in mind. Having eight courses would give students more credit opportunities in order to be able to graduate.

“Do we want to use the block to manipulate the graduation rates, or to actually help these kids?” Weintraub said.

Many teachers and students also voiced their dislike for long periods. Teachers vocalized how difficult it is to engage students and keep them interested during the daily long block, and students also said that it is difficult to pay attention for so long, and that long blocks get tedious.

Furthermore, students only see their teachers every other day. A block schedule would deprive them of the constant reinforcement needed for difficult classes, and any problems or questions left over from class would not be addressed until two days later.

“Meeting with teachers for one day out of the two day cycle means that students will lose consistency in their classes. I would only see my teachers two or three times a week. For example, if I am having trouble with a reading assignment of homework problem I would have to wait two days to address my issue with my teacher,” Gada said.

The voice of the custodial staff also was heard in the discussion. Joseph Atani, a custodian at Stamford High School, contended that block scheduling comes with a modified cleaning schedule. Project work would be eliminated, maintenance reduced, and problems related to building management increased. Any cleaning or maintenance not finished in the reduced time period allotted would be left over for the next day.

“What we leave today will be there tomorrow…how are we going to catch up?” Atani said.

“This plan might work for other districts, but we are not those other districts,” Adalia Huarez (’22) said.

At the meeting, a general consensus regarding block scheduling of the speakers was that there are no benefits, that it places an additional workload on teachers and custodians, and that 88 minute-long periods are instructionally problematic to teachers and students.

Once the meeting was adjourned, a remark was made that there ought to have been a break, as the meeting was too lengthy. It lasted around 90 minutes.

The contents of this article were edited to correct a missing link and citation regarding the AITE/Advocate Article by Campbell Beaver. The Westword strives for accuracy and correct attribution of the information in its articles, and we would like to extend our sincerest apology to the author and the publication. -Mr. von Wahlde, Adviser