*If you wish to keep reading, keep in mind that there may be spoilers!*

While there are endless amounts of wonderfully crafted books for the world to enjoy, The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is one of the few that sticks to your soul like dog hair to your black clothing; it never really goes away. It leaves a lasting impact on the reader.

The novel features a young girl by the name of Liesel Meminger, who is taken in as a foster child in Nazi Germany. Throughout the years, she grows from an illiterate, yet incredibly intuitive girl to a courageous, book-snatching teen with a big heart. She meets a cast of characters in a scene only tragedy can bring, and still becomes the kind of person the world doesn’t deserve in a place where hatred grows from the very things she loves most: words.

Markus Zusak is an incredibly gifted writer, and as a result, The Book Thief has inspired some fantastic works of art.

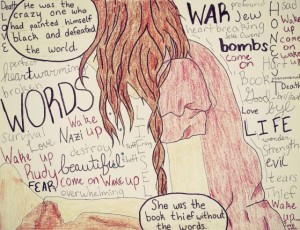

Photo CC: Devinart user Pebbled

Arguably, the most important of the topics the novel presents is the power of words. Words move people much more efficiently than firepower ever will. So, while the words surrounding the drawing of Liesel Meminger are centered on her friendship with Rudy Steiner, the art also shows how much her life revolves around words and in turn, how the words of the novel revolve around her. While the drawing is one of the first things you see, the use of the bolder letters highlights what the story is really about: war, death, life, love, and words.

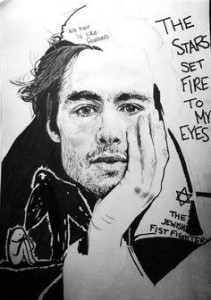

Photo CC: Pinterest user Grover Davis

Another one of the characters highlighted in the story is Max Vandenburg, the Jewish fist fighter who finds refuge in the Hubermann basement on Himmel Street. This happens to be the very same house Liesel comes to call home. Not only is the artwork a near perfect representation of the character (with the actor, Ben Schnetzer’s, photograph being used as reference), but the additions of the book and movie quotes (“His hair is like feathers…” and “The stars set fire to my [his] eyes,”) make the drawing instantly recognizable to fans. They add characterization and significance. The viewer knows immediately who he is without ever needing to read “Max Vandenburg”. Finally, by putting in the illustrations from The Standover Man, one can also connect the work to Max’s connection with Liesel, and how he inspired her to write and give her a new perspective on how cruel life in Nazi Germany could be.

Photo CC: thewordshakertree

This piece beautifully brings another theme, childhood, to the table. Rudy Steiner is a part of what keeps Liesel sane throughout the events that alter her life forever, from her first appearance on Himmel Street to Max’s arrival at house thirty-three to her foster father being conscripted. The duo spent most of their time stirring up mischief, whether it be stealing from local farmers or just generally being rebellious. Liesel would steal books constantly in an effort to satisfy her interest in literature along with Max. Up until much later in the novel, the boy is a major reason why Liesel didn’t have to grow up so fast. Despite hiding a Jew in her basement and being faced with so many losses in her young age, she was still able to be a girl. The above image shows the content that the lazy summer days would bring Liesel, and how even in a place many people associate with evil, and even though the characters are short on food and starved of money, there are still things that people can be happy about.

Photo CC: Pinterest

Finally, these images created for each character of the book are incredibly true to the book. Death, the narrator, is always insistent that he/she does not carry a sickle or a scythe, and only don a black robe for the colder days. While many artistic representations are exactly that, in this piece, the man appears rather casual. “Agreeable. Affable. And that’s only the A’s.” At the same time, the saddened expression also illustrates that Death does indeed, have some concept of emotion, as described in the novel (for instance, how our narrator can never stick around to watch the survivors).

Moving onto Liesel, one can clearly see the almost shy version of herself that is more present in the beginning of the story. At the same time, with her book and closed-off position, you can also interpret the shyness as the caution or concern displayed when Max is in hiding. The book finishes the characterization; you can’t be a book thief without a good book or two.

As for Rudy, his coltish display of mischief sums up Zusak’s descriptions in one cartoonish image. Even his clothing and lemon yellow hair are looking worse for wear, and growing up on the poor side of town certainly means a lack of fancier clothing.

Max Vandenburg is, as one would expect of a man on the run, a little rough around the edges. His feather like hair, the unshaved face, the ragged clothing and thin structure all indicate something Zusak drew in his chapters. You can still see his caring nature, especially towards the young Rudy and Liesel, through his slightly bent position and wide smile.

Hans Hubermann is Liesel’s beloved foster father. He is often described as a dangerously generous man. Who else would hide a Jew in a place flooded with Nazis? He is happiest with a cigarette slouching on his lips and an accordion breathing between his arms. Due to his kindness and compassion, Liesel immediately takes a liking to him, and it shows in the drawing from the man’s joyous expression the accordion’s bellows exhale the music.

Finally, Rosa Hubermann (Liesel’s foster mother and Hans’ wife) is shown. Zusak paints her as a wardrobe of a woman with a waddle to her walk and sharpness to her tongue. Nonetheless, she deep down kind hearted and “a good woman for a crisis.” The wooden spoon coupled with the almost sour expression captures the tough love attitude of the character, and from the way Hans still leans into her while she scolds him, it is easy to see that underneath the rough exterior is a soft soul.